Building an Intelligent Water Balance Sankey Chart System

Water is the lifeblood of any industrial facility. Every drop that enters a plant embarks on a journey through treatment systems, storage tanks, and consumption points before it either leaves as product, evaporates into the atmosphere, or disappears into the mysterious realm of “unaccounted losses.” For facility managers, understanding this journey isn’t just about conservation, it’s about operational intelligence, cost control, and regulatory compliance.

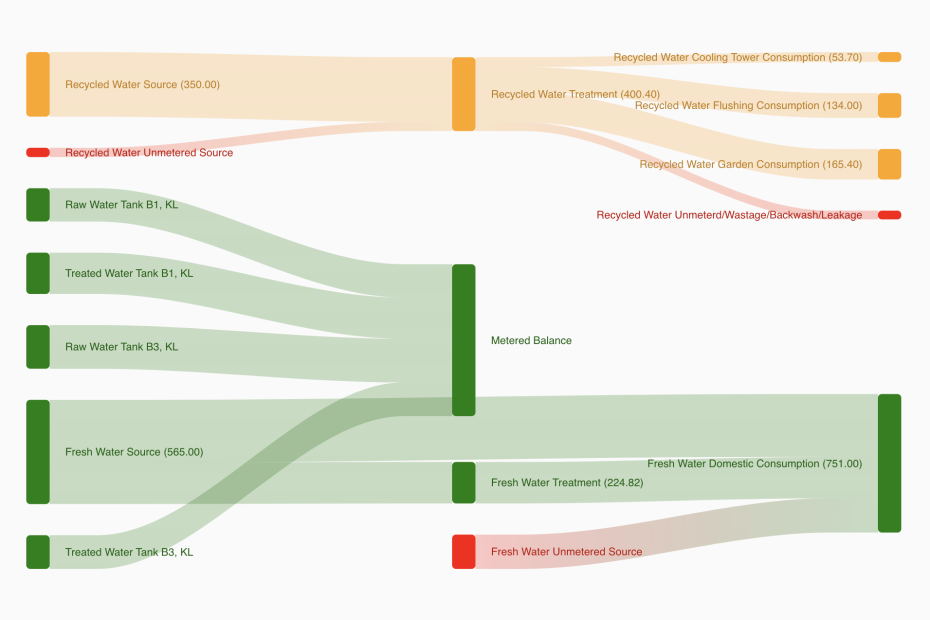

The challenge we faced was deceptively simple: build a visualization that shows exactly where water comes from, where it goes, and most importantly, where it vanishes. The solution? A Sankey diagram those elegant flow visualizations where the width of each band represents the quantity flowing through the system. But transforming raw meter data into a meaningful Sankey chart turned out to be a masterclass in handling real-world data chaos.

Understanding the Dual-Stream Reality

Modern industrial facilities don’t have a single water system, they have at least two parallel universes operating simultaneously. Fresh water flows through the Water Treatment Plant (WTP), while recycled water courses through the Sewage Treatment Plant (STP). Each stream has its own sources, treatment stages, and consumption endpoints.

Our first architectural decision was treating these as independent flow networks that could be visualized side by side, each telling its own story while contributing to the facility’s overall water narrative.

The elegance of this separation became apparent during implementation. A WTP might source water from municipal supply, bore wells, and tanker deliveries. The STP, meanwhile, collects wastewater from various processes and transforms it into reusable water for cooling towers, landscaping, or process applications. By maintaining distinct processing pipelines, the visualization could reveal patterns unique to each system, perhaps the STP operates efficiently while the WTP shows significant losses, or vice versa.

The Taxonomy of Flow

Every meter in the system carries a tag, a semantic label that declares its purpose in the water journey. These tags follow a deliberate naming convention: stp_source, wtp_treatment, consumption. This taxonomy might seem bureaucratic, but it’s the foundation that allows automatic flow routing. When a new meter comes online, simply assigning the appropriate tag integrates it into the visualization without any code changes.

The classification system recognizes three fundamental stages in the water lifecycle:

- Source nodes represent water entering the system – municipal connections, bore wells, tanker unloading points, or collected rainwater

- Treatment nodes capture the transformation stage where raw water becomes usable, or wastewater becomes recyclable

- Consumption nodes mark the final destinations – cooling towers, process equipment, landscaping, or discharge points

What makes this taxonomy powerful is its flexibility. A meter tagged as consumption without a WTP or STP prefix automatically routes to freshwater consumption. The system gracefully handles edge cases where water bypasses treatment entirely, a direct line from a bore well to a cooling tower, for instance.

The Meter Aggregation Challenge

Here’s where reality diverges from textbook data modeling. In an ideal world, each Sankey node would correspond to exactly one flow meter. In practice, a single logical node, say, “Cooling Tower Makeup”, might aggregate readings from three different meters serving different sections of the same system.

The solution involved intelligent grouping by tag labels. When multiple meters share the same semantic tag, their readings accumulate into a single node. This aggregation happens transparently, preserving the conceptual clarity of the Sankey while accurately representing total flows.

But aggregation introduced its own subtlety: what label should appear on the node? For single-facility views, showing individual meter names provides operational detail. For multi-facility dashboards, the semantic tag label creates meaningful comparisons across sites. The system dynamically chooses based on context, a small detail that dramatically improves usability.

The Art of Flow Allocation

Now we arrive at the heart of the engineering challenge: connecting sources to treatments to consumption points. A Sankey diagram isn’t just a collection of nodes, it’s the flows between them that tell the story. And here’s the uncomfortable truth: real-world meter deployments rarely provide complete flow instrumentation.

Consider a facility with two bore wells feeding a single treatment plant. If only the bore wells have meters, we know the total input but can’t directly measure the output. The treatment plant might feed six different consumption points, but only three have meters. How do we draw the connecting flows?

The solution embraces a principle of progressive allocation. Starting from sources, we allocate flow to treatment nodes based on available capacity. Each node maintains an internal ledger tracking its inflows and outflows. When a source has remaining capacity and a treatment node needs more input, they connect. The process then cascades from treatment to consumption using the same logic.

This cascade produces flows that respect conservation laws, water can’t appear from nowhere or vanish without trace. Well, it can vanish, but that’s precisely what we want to highlight.

Exposing the Invisible: Unmetered Sources and Losses

The most powerful feature of the system isn’t what it measures, it’s what it infers. When consumption nodes report higher totals than their incoming flows can explain, mathematics reveals an uncomfortable truth: there’s water entering the system from unmeasured sources.

Similarly, when treatment plant output exceeds the sum of metered consumption, the difference represents unmetered balance, water that’s going somewhere, but we can’t say where. Losses? Leaks? Unmetered irrigation? The visualization doesn’t speculate, but it makes the discrepancy impossible to ignore.

These phantom flows appear as distinct nodes, color-coded in attention-grabbing red. “WTP Unmetered Source” and “STP Unmetered Balance” become conversation starters in operational reviews. Often, they lead to meter installations that finally close the measurement gap. Sometimes they reveal actual losses that justify infrastructure investments.

The Bypass Detection Algorithm

Water systems are designed with treatment as a central processing step. But what happens when reality includes bypass lines? Perhaps emergency protocols allow raw water to flow directly to certain processes. Perhaps someone installed a shortcut that was never documented.

The allocation algorithm detects these scenarios automatically. After flowing water from sources through treatment, it examines whether sources still have unallocated capacity while consumption nodes remain undersupplied. When both conditions exist, the system infers a direct bypass and creates a flow labeled “Potential Direct Bypass to Consumption.”

This isn’t an accusation, it’s a hypothesis made visible. The label deliberately uses “potential” because the inference could reflect actual bypasses, metering errors, or timing mismatches. But making the hypothesis visible enables investigation. More than once, these inferred bypasses led to discovering undocumented infrastructure that explained long-standing water balance discrepancies.

The Level Meter Integration

Flow meters tell you about movement. Level meters in storage tanks tell you about accumulation. Both matter for water balance.

The system integrates level meter data by calculating the difference between starting and ending tank levels across the reporting period. This difference, multiplied by tank surface area, yields the net volume change. A tank that starts full and ends empty contributed water to the system even if no flow meter tracked the discharge.

This integration solves a persistent challenge in water accounting: storage buffers that decouple supply timing from consumption timing. Daily flow totals might balance perfectly while hiding significant storage swings within the day. By including level-derived quantities, the visualization captures these dynamics.

The Single View Scaling Challenge

Building a visualization that works at one scale is straightforward. Building one that remains meaningful across scales, from a single facility’s detailed view to a multi-site executive dashboard, requires thoughtful design.

At the facility level, operators want meter-specific labels. They know that “Bore Well 3” has been problematic and want to see its contribution distinctly. At the portfolio level, executives want semantic categories. They don’t care which bore well contributes what; they want to compare total groundwater dependency across sites.

The labeling logic dynamically adapts based on scope. Single-facility views promote meter names to node labels. Multi-facility views use tag categories, creating meaningful aggregations that support cross-site comparison. This contextual adaptation happens automatically based on the query parameters, requiring no user configuration.

Handling Data Quality Gracefully

Real meter data is messy. Meters go offline. Communication failures create gaps. Calibration drift introduces systematic errors. A water balance system that demands perfect data would be perpetually broken.

The implementation adopts a philosophy of graceful degradation. Zero-value readings filter out automatically, if a meter reports nothing for the period, it doesn’t clutter the visualization with useless nodes. Missing start or end values for level calculations yield zero contributions rather than errors.

Perhaps most importantly, the system proceeds with available data rather than failing on incomplete data. An analyst investigating a specific facility shouldn’t be blocked by a malfunctioning meter at a different site included in the query scope.

The Presentation Layer Decisions

Sankey diagrams offer considerable stylistic latitude. Colors, node positions, label placement, and flow curvature all affect readability. Our implementation made deliberate choices optimized for water industry conventions.

WTP flows render in green, the universal color of environmental responsibility and freshwater. STP flows appear in amber, suggesting the recycled nature of the water without implying contamination. Problem indicators, unmetered sources and unexplained losses, appear in red, demanding attention without requiring legend consultation.

Node labels include quantity values directly, eliminating the need for hover interactions to understand magnitudes. The format “Cooling Tower (1,234.56)” immediately conveys both identity and scale. This verbosity costs visual cleanliness but gains operational utility.

Lessons for the Water-Curious Developer

Building this system revealed principles that extend beyond water management:

Embrace incomplete instrumentation. Real-world measurement systems have gaps. Design algorithms that reveal gaps rather than hiding them, turning missing data into actionable insights.

Let taxonomy drive architecture. The tag-based classification system meant new meters integrate without code changes. When domain experts can extend the system through configuration, adoption accelerates.

Make inference visible. The bypass detection and unmetered flow calculations generate hypotheses, not facts. Labeling them as such builds trust and encourages investigation rather than blind acceptance.

Design for multiple scales simultaneously. A visualization that only works at one zoom level will frustrate users who need different perspectives. Build contextual adaptation into the foundation.

Respect conservation laws. In any balance calculation, totals must reconcile. Designing allocation algorithms around conservation constraints catches errors early and produces physically meaningful results.

The Ongoing Journey

Water balance visualization isn’t a destination, it’s an ongoing practice. Deployments surface questions that drive instrumentation improvements. As instrumentation improves, new patterns emerge that prompt operational changes. Those changes shift the balance and call for fresh analysis.

The Sankey chart serves as a conversation catalyst in this cycle. It transforms abstract flow data into spatial relationships that anyone can understand. The facility manager sees where investment in leak detection might pay off. The sustainability officer identifies opportunities for increased water recycling. The operations team spots anomalies that suggest equipment problems before they become failures.

In the end, making water flow visible is really about making decisions visible, showing stakeholders exactly how their facility uses its most precious resource, and where opportunities for improvement might flow.

Building systems that reveal hidden patterns in operational data is both technically challenging and deeply satisfying. The water balance Sankey chart exemplifies how thoughtful data transformation can convert raw meter readings into strategic insights, making the invisible visible, one flow at a time.

Software engineer working as a full stack developer.